Random Recollections of the Leicester Secular Society

by Sydney A. Gimson

This webpage comprises Sydney A. Gimson's Random Recollections of the Leicester Secular Society, with Digressions, Part I, written March 1932. The original typescript is kept at the Leicester Records Office, Wigston.

Now that I have passed the age of 70 years and the Leicester Secular Hall, with which I have been connected for so long, celebrated the 50th anniversary of its opening on March 6th 1931, my conversation with members of the Leicester Secular Society naturally becomes more and more saturated with tales of the happenings in the years gone by. I am told by my friends in the Society that many of these stories are interesting to them, some are even of considerable importance in the History of the Society, and I am urged to write them down for the use and amusement of those who come after me. I hesitate, for I have no literary gift, but I will see what I can do. I have no expectation that my mostly trivial recollections will have any interest except for a few of my friends and the members of the Society which has for so long kept the flag of Freethought flying in the town of Leicester.

My recollections of Freethinkers begin some time before I knew what the word meant. My father was a Freethinker long before I was born. In No.9 of The Movement, edited by G. J. Holyoake and published February 10th 1844, there is mention of a branch of the ‘Rational Society’ in Leicester, and a subscription of 1/- from Mr. Gimson to the Anti-persecution Society is acknowledged. No doubt that Mr. Gimson was my father. Mr. Holyoake often stayed with my father and mother, and his friendly presence in the home is one of my earliest recollections.

I think the first Secular Society lecture which I attended was given by Dr. Alexander V. W. Bikkers (a Dutchman) in the small lecture hall of the Temperance Hall, in January 1877. He also stayed in our house and he gave me a little book which he had written Anno Domini 2071 containing some cute prophecies as to developments in 200 years.

In those days I did not call myself a Secularist. My mother went to the Great Meeting Chapel, Unitarian, and I went with her. There I ‘sat under’ the Rev. C. C. Coe, Rev. Laird Collyer and Rev. John Page Hopps. When Mr. Coe was at Great Meeting I was too young to have definite views about him or his teaching. The Rev. Laird Collyer had an attractive personality. He was very dramatic in his preaching and praying and always reminded me of Henry Irving.

I came much under the influence of Mr. Hopps, with his fine, strong and sympathetic character. It was, however, his broad radicalism rather than his religion which drew me to him, for, as I reached ‘years of discretion’ I was beginning to understand and value the Secularism for which my father worked. At one time I was an ardent Unitarian and, with the confidence and arrogance of youth, would argue with my father that the existence of a Creator and a life after death for all of us were scarcely open to doubt. At the moment of the discussions I would feel that I had the best of it! But afterwards, in the quiet of my own room, or lying awake in bed and thinking them over, I was not so sure that my arguments would bear careful examination, and doubts began to grow.

I was then working fairly hard at the Great Meeting. Teaching in the Sunday School from when I was 18 and onwards, helping with the Social Union (Secretary for several years) and the production of plays for the Christmas Parties, in which I usually acted, and regularly attending the Sunday morning services in the Chapel. I also did some teaching in evening classes on week-days under the Domestic Missionary.

To show what slight things may have a strong influence, when I was about 21 I read a book by an author whose writings have always been attractive to me, George Macdonald. I think it was Robert Falconer. An incident is described where two friends are on a walking tour and sleep one night in the same room. The younger one kneels down in prayer before getting into bed. He notices that the elder one, who is something of a hero to him, does not pray, and asks him whether he does not believe in prayer. The older man tells him that he has a deep belief in prayer; and often prays, but that the feeling of need for prayer does not come at regular intervals so that he has long given up the habit of praying every night just before getting into bed! Up to this time I had regularly ‘said my prayers’ before lying down to sleep but the argument seemed to me so reasonable that I gave up the habit from the day I read that passage. I fancy that the hold of religious beliefs upon my mind must have been growing very weak for, from that day to this, I have never felt the need or desire for prayer.

Before I was 20 I was growing more sympathetic to my father's views and was much interested in the conversations I heard between him and the leading Freethinkers who visited our home. I am not sure of the exact date, but it must have been in the very late seventies, Mrs. Besant stayed for a week with us. She was then a charming, brilliant, very good-looking young woman, and her conversation was a delight. I did not hear her lecture at that time. During this week a Unitarian Minister, the Rev. Mr. Binns, I think from Liverpool, stayed a day or two with us. He was something of a ‘character’, very able and with a strong but curious sense of humour. There was much good-humoured sparring between the two, which was a joy to the listeners. Also during this week I can remember that Charles Bradlaugh dined with us at least once. His courtesy and dignity much impressed me, and I got an abiding impression of his ‘bigness’, both physical and intellectual. One felt that one was in the company of a great man.

Other visitors about that time were G. W. Foote, Charles Watts and Mrs. Watts (‘Kate Carlyon’), with her happy recitations, Joseph Symes, James Thomson (the poet), George Jacob Holyoake frequently, and Larner Sugden, of Leek, who was architect for the new Secular Hall which was being built in 1880.

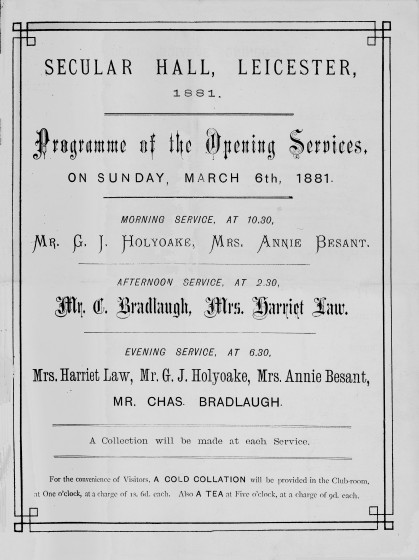

On the first Sunday in March (6th.) 1881, came the opening of the new Secular Hall in Humberstone Gate. The Hall did not belong to the Society but was built by a Limited Company (The Leicester Secular Hall Co. Ltd.) all the shareholders of which were Secularists, my father holding the largest number of shares. This company had been in existence for about ten years, gradually gathering sufficient money to build the Hall and there was great rejoicing when the great day of the opening came at last. Besides the Hall the company owned considerable property surrounding it.

On the day of opening, although I was not then a member, I attended all three meetings, morning, afternoon and night, and still have a vivid memory of the excitement and rejoicing that characterised each. Many of the leaders of the movement were there. In the morning my father gave the inaugural address. Mrs. Annie Besant and George Jacob Holyoake also spoke. In the afternoon Theodore Wright presided and Charles Bradlaugh and Mrs. Harriet Law spoke. R. A. Cooper of Norwich took the chair at the evening meeting; this was so crowded that an overflow meeting was held in the club room, where the speeches were repeated. Charles Bradlaugh, Mrs. Besant and G. J. Holyoake spoke.

For the opening of the Hall, James Thomson (‘B. V.’ of the National Reformer) had written a poem which was finely recited at each meeting by Mrs. Theodore Wright. Altogether a great day, well remembered by all who were present.

I have but indefinite recollections of the next two and a half years, except that for a time I taught in both the Great Meeting and the Secular Society Sunday Schools, morning in one and afternoon in the other: rather too strenuous a way of spending the Day of Rest! But I am glad that I did it for it gave my father definite evidence that I was being drawn to the Secular Society, though I did not become a member until after his death. Judging from my own feelings I am sure that knowledge of the way I was going would give him pleasure. I also remember that a conference of the short-lived ‘British Secular Union’, which was set up by dissentients as an alternative to ‘The National Secular Society’, was held in the Hall. Stewart Ross (‘Saladin’) was there and also the Marquis of Queensberry. On the principle that every Radical loves a Lord I suppose we were somewhat thrilled to find a Marquis among us. He had recently published an agnostic poem.

Much discussion was aroused in Leicester because a bust of Jesus was placed on the front of the Secular Hall alongside those of Socrates, Voltaire, Thomas Paine and Robert Owen. Ministers and clergymen raised objections and protested strongly and even violently. Canon D. J. Vaughan of St. Martins expressed his alarm at the opening of the Hall, and his displeasure at the presence of the bust of Jesus, in plain terms and frequently. No doubt my father was responsible for the inclusion of this bust. The real Secularism of the teachings of Jesus was much in his mind those days. I need only give the titles of two of his lectures to enable any-one to understand his position, Jesus Christ: a Witness for Secularism and against doctrinal Christianity, and The Ethical Teachings of Christ testify to the all-sufficiency of Secular Conduct.

Soon after the Hall was opened the Secular Society entered upon a period of trouble and trial. On September 18th 1881, Michael Wright died. He was a very close friend of my father's and the two had been for many years associated in work for the Secular Society and in the building of the Hall. I have always believed that he and my father were the two outstanding personalities in the Society. Mr. Wright was at one time manager to the firm of Hodges & Sons, Elastic Web Manufacturers on the Welford Road. He had a house by the side of their gates and we lived next door to him (No.39) until 1871. Later he started an Elastic Web business of his own in Leicester, but soon removed to Quorn where the business flourished and has continued to flourish up to today, under the management of his sons and grandsons. I shall have occasion to refer to his sons later, for they were all good friends to our Society.

His death was a great loss, and then followed, September 6th. 1883, the death of my father. He had been hopelessly ill for some time and wished for the end. That day I had gone to a near-by village in the morning to attend the wedding of a girl cousin and returned in the evening to find him dead. At first one could not realise the blank that was left, though I knew that it was not only my father, but a truly big man who was gone. My brother, Ernest, and I went down to Secular Hall to give the news.

On the way back I remember that we saw a crowd on the London Road and found that they were watching two men fighting. With the rash confidence of youth we forced our way through and succeeded in separating them. I suppose this sticks in my memory because that day was always to be remembered as a day of tragedy. At the time of his death father was a member of the Town Council, on which he had been sitting since November 26th 1877, as a Liberal representative of West St. Mary's Ward. At his election religious prejudice was violently excited against him but, and this showed his great personal popularity in the town, he secured a record majority of votes.

Not very long afterwards two more of the old and prominent members of the Society died: Mr. Thomas Coltman, a Past President, and Mr. Sladen of Sladen's Indigo Dye Works, who was also a Town Councillor.

This left the Society in the control of its younger members. I had joined the Society in the autumn of 1883, being introduced to the Committee by Philip Wright, eldest son of Michael Wright and a fine faithful friend of the Society. In 1884 Thomas Wright, youngest son of Michael Wright, was President and I was Secretary. With the help of a good Committee we did our best to guide the Society wisely but were very inexperienced. Father had left �100 per year for 10 years to help the finances but even then we had difficulty in making both ends meet and only succeeded by means of whipping up special subscriptions and holding periodical Bazaars. We were happy in having for a landlord a sympathetic Company which waited with exemplary patience when the very low rent was not forthcoming.

In pursuance of the policy of making our platform free for the expression of all seriously held opinions arrangements had been made before my father's death for a number of young clergymen, members of the Guild of St. Matthew, to lecture to our audiences on Sunday evenings in the autumn of 1883. Father had asked my mother to send a sovereign to be put in the collection basket at each of these lectures and I had the pleasure of taking this.

The leading spirit of the Guild was Stewart Headlam, who, although an earnest churchman, was always a firm and active supporter of Freedom of Opinion and the expression of it. Other members who lectured for us were the Rev. J. C. Denison, Rev. C. E. Escreet, Canon H. C. Shuttleworth, Rev. Brooke Lambert (Vicar of Greenwich), Rev. F. W. Ford, Rev. J. E. Symes (Professor of Economics at Nottingham University College), Mr. F. Verinder and several other laymen. I cannot remember the exact wording but I believe the object of the Guild was stated to be the ‘Reconcilation of the People of England to the Church’. I am not aware of any of our people being reconciled to the Church but we could and did like the men who came to us, and their obvious sincerity. We liked them so well that several of them, notably the Rev. Stewart Headlam, came again and again, and sent other members of their Guild.

One of the most welcome of these was the Rev. C. W. Stubbs, then Vicar of Granborough, later Dean of Ely, and later still Bishop of Truro. He came to us at least once while he was Dean of Ely but was not able to do so when he was Bishop of Truro. He once lectured to us on The Religion of Shakespeare and was frank enough to say that he could find no evidence in the plays that Shakespeare had any religion except ‘The Religion of Humanity’.

Brooke Lambert was specially a student and lover of the Works of Plato. One of his lectures was on The Republic of Plato and the Republic of Christ. He once said to me that one of his predecessors in the Vicarship of Greenwich could have translated Plato if he would (being a fine scholar) another did translate Plato and he himself would have translated Plato if he could!

Mr. Escreet urged us to start Sunday Cricket and through his suggestion our young men started those games on The Pasture which are well described in Mr. Gould's little History of our Society. For some reason which I now forget I did not join in those games. I think I must have been away from Leicester. I am quite sure I was heartily in favour of them.

Though generally welcome, the visits of these clergymen did not meet with universal approval and one night, after I had defended some part of the lecture in the discussion which followed it, as the audience filed out of the Hall, my brother, Ernest, heard one of our members say ‘Sydney's getting too fond of these damned parsons!’.

Frequent visitors in the ‘Eighties’ were a number of old friends of my father's. George Jacob Holyoake with his small, rather squeaky, voice and his closely reasoned, well phrased and witty lectures. Though I well liked and greatly admired Mr. Holyoake and saw his great ability, I could not always agree with him, and I felt that he was somewhat inclined to rejoice too soon at friendly approaches of the Great Ones of the Earth and to see breadth of mind where I could see only condescension or calculation. But he was a great Freethinker and always a good friend to our Society.

G. W. Foote, for whose early magazines my father had provided a good deal of capital, who delivered fine fighting lectures which always had a dignified literary form. He had a deep musical voice and delighted in reciting bits of Shakespeare or reading treasured passages from the Poets.

Charles Watts whose lectures could truly be called ‘Orations’, they generally contained several perorations and occasionally the audience was deceived into thinking he had reached the end of the lecture long before he was ready to sit down! J. H. Levy (‘D.’ or ‘Dialecticus’ of the National Reformer) giving learned lectures on Economics or Biblical Criticism.

That somewhat truculent speaker Joseph Symes, who seemed surprisingly violent for a man who had been a Methodist minister but who had a lovable personality. He was the first man that I remember to have lectured in the Hall and put forward the view that Jesus never existed. At the time that idea seemed to me to be absurd and I fear I was a bit unreasonable in the following discussion, but my outlook has changed since John M. Robertson wrote and spoke on the question.

Mrs. Theodore Wright and Mrs. Charles Watts often came to give us evenings of Recitations and Readings. When Mrs. Wright became so famous on the London stage, especially in the plays of Ibsen with Beerbohm Tree and others, and in The Knight of the Burning Pestle we rejoiced with her, and when J. L. Toole, that irresistible comedian, came to Leicester many of us had an added enjoyment in seeing Mrs. Charles Watts (Kate Carlyon) in his Company.

I must not forget Mr. F. Feroza, an Indian gentleman, I think Parsee, one of the most eloquent and forceful speakers I have ever heard. One could never forget the effect of one of his philosophical lectures, a joy to listen to and convincing in argument. We were sure of a crowded Hall whenever he came.

Another of the older group of first-rate Secularist lecturers was Touzeau Parris, who had been Unitarian Chaplain to Samuel Courtauld. His speciality when I heard him were lectures based on the original meanings or derivations of words and phrases, always interesting and suggestive. I remember that once, before I had joined the Society, my father came home from a visit to the Hall where he had gone to hear Charles Bradlaugh. He told us that Bradlaugh had been unable to come but they had had a first rate lecture from ‘a young man named Touzeau Parris’ who had been sent down as a substitute. Late in life Mr. Parris fell upon hard times and a committee was formed to collect funds to help him. On the committee were Mrs. Bonner, G. W. Foote, J. M. Robertson, G. Bernard Shaw, Charles Watts, F. J. Gould, and myself. I think we got just under �300 for him. George Meredith was one of the subscribers and I still treasure the autograph note that he sent with his gift. Mr. Parris died October 28th 1907, aged 68, before the fund was completed, and the balance left was sent to Mrs. Parris.

After I was married, in April 1886, most of the lecturers stayed with us and I have recollections of many delightful hours spent in my smokeroom library talking and gossiping with men that it was a joy to meet, though occasionally one happened on a visitor that it was a joy to say ‘good-bye’ to! Still, I count it the greatest privilege of our married life to have been able to come into contact with and to know so many able and distinguished men and women, truly of ‘All sorts and conditions’. The fault was ours if our minds were not broadened and enlightened. All this pleasure and opportunity we owed to my connection with our Secular Society and were duly grateful.

Among the lecturers of this early period came an interesting little group from Nottingham, Harry Snell, who has been a frequent and very welcome visitor ever since and always a close personal friend of mine, who is now Lord Snell of Plumstead and was Parliamentary Under-Secretary for India. J. B. Coppock who for a good many years gave us interesting scientific lectures. Arthur Hunt [Mr Gimson just mentions the name without further details]. A. R. Atkey, who has since been Conservative M.P. for one of the Nottingham divisions, and, later, Lord Mayor of Nottingham. And, I think, others whose names I have forgotten. I do not know the reason why Nottingham was so prolific in Freethought speakers at this time. Leicester has not produced one who has had any position of importance. I am bot forgetting that we are proud that Chapman Cohen was born in Leicester, but we can hardly claim to have ‘produced’ him as speaker and leader, for he left Leicester when quite a child.

Among the younger men who lectured for us in the late eighties or early nineties were Arthur Moss, John M. Robertson (I think he first lectured for us in 1886 or 87, and then began a friendship which has been invaluable to me and influenced all the rest of my life, I shall have more to say of this later), George Bernard Shaw (the first record I can find of a lecture by him is on Dec. 6. 1885), and Chapman Cohen (Dec. 31. 1893 is the first record I can find but I fancy he spoke in our Hall before then.) All are still living and active today, March, 1932.

I have a lecture list for October, November and December, 1885, which shows that variety of subjects which it has always been our policy to arrange. Here is the very interesting list of speakers:— J. H. Levy, Rev. J. E. Symes, W. W. Collins, Thos. Slater, F. Feroza, Rev. Brooke Lambert, Henry Crompton (Positivist), William Morris, Rev. Stewart Headlam, G. B. Shaw, Rev. C. L. Marson, and Mrs E. Marx Aveling (daughter of Karl Marx). What would we give to hear such a series within three months now? But some of our present lists will take a bit of beating.

In addition to all the above we engaged Charles Bradlaugh for a lecture on Wednesday, Oct. 28th [1885]. There was no man in England then, with the exception of Mr. Gladstone, who drew such great crowds to hear him. We knew that the Secular Hall, with its seating accommodation of under 600, was no use, so we took the biggest hall in Leicester, the Floral Hall, with seating accommodation of 2,000 to 2,500, and considerable standing space in the promenade gallery. One shilling for first seats and sixpence for second were changed, and the hall was crammed full. We estimated that 3,000 were there.

I remember an incident which showed something of Mr. Bradlaugh's personality and his insistence on orderly behaviour at his meetings. After the Chairman (I do not remember who it was) had shortly introduced him Bradlaugh stood up. Instead of beginning his speech he quietly said that he noticed a good many men were smoking and, as ladies were present, he asked them not to do so, and sat down. Of course nearly every smoker put away his pipe, but about a dozen kept on. Again Mr. Bradlaugh jumped up and, in more peremptory tones, asked that all smoking should cease, and sat down. Then all stopped except one determined man in the gallery who leant over the front and still puffed away at his pipe! This time Mr. Bradlaugh jumped up and, pointing a finger at the offender, told him in ringing tones that he was holding up the meeting and that the speech would not begin until his pipe was out! I believe then that a neighbour snatched away the pipe, and we thought there might be a row, but all was quiet, the speech began and we listened entranced for over an hour in wonderful silence except for the ringing applause which frequently followed the telling arguments or the vivid illustrations or the eloquent passages. At the end came a storm of applause and we all came away feeling that one of the great events of our lives was over. It has remained a great memory for me ever since.

An incident of this visit has naturally kept vivid in my memory. At that time I was engaged, and had been since the Spring of 1884, to Jeannie Lovibond, youngest daughter of Mr. John Lovibond of Starts Hill, Farnborough, Kent. When I went through the terrifying experience of interviewing her parents it was much on my mind that my freethought opinions might be a handicap. To my great relief I found that Mr. Lovibond was tarred with the same brush and quite enjoyed talking over heresies with me. He and Mrs. Lovibond had for some years formed a strong friendship with my father and mother. At the time of Mr. Bradlaugh's visit they were staying with my mother. Mr. Lovibond came down to the Secular Hall to a tea which we had there to give our members an opportunity to meet Bradlaugh before the Floral Hall meeting. I there introduced them and they had a little chat. Mr. Bradlaugh, with his fine courtesy and natural dignity, charmed Mr. Lovibond who came to me and said: “My boy you must get me a seat on the Platform to-night, I want to show that I'm proud to support such a man.” This I succeeded in doing. Mr. Lovibond, with his strong, rugged face, thick crop of snow white hair and beard, was a striking figure on the platform, curiously like a celebrated Frenchman of the day. After the meeting was over many came to me and asked: “Who was that old gentleman on the platform who looked just like Victor Hugo?”

I have an interestng letter from Bradlaugh to my father, written from the National Reformer Office at 29, Turner St., London, E., and dated May 25. 1876, in which he says: “Can you kindly favour me with any short form of words which added to our 4 principles would make your suggestion effective. Mrs. Besant, with whom I have talked over your letter, thinks that the insertion of ‘in this world’ after the word ‘happiness’ in No. 1 and the addition of the following as Clause 2 would meet the case – The others standing as they now do but numbered 3, 4, & 5. – No. 2. That reason and experience are the only wise guides of man, and that Secularism therefore recognises nothing outside nature, is scientific in its method, utilitarian in its morality.”

On the death of Bradlaugh in 1891 ten of our members, of whom I was one, attended his funeral at Woking. It was the most impressive funeral I have ever attended. Thousands were there from far and near. There were no speeches but the coffin was laid upon the ground by the side of the prepared grave, a lengthy queue was formed and the crowd filed by in silence to pay a last tribute to their great and beloved leader.

When I frst began working with our Secular Society there was a group of earnest members of the Society who belonged to the Positivist movement. Some of them formed the backbone of our Sunday School. I think I may say that the leader was Mr. Findley, a second-hand bookseller living over his shop in High Street. He had folowed his father in the business and they were both well known men, much respected in the town. Though not belonging to the group (which included Mr. Franks and Mr. Cornish; the latter fortunately still an honoured member of our Society) I was often invited to meetings at Mr. Findley's home where I met Dr. Congreve, Dr. Carson, Mr. Henry Crompton and others and was much impressed by their learning and humanity; they were charming people whom it was a privilege to know. Dr. Carson and Mr. Crompton lectured in our Hall. I cannot remember that Dr. Congreve ever did so.

Dr. Carson and Mr. Crompton stayed with my wife and me more than once. I remember that Mr. Crompton told us that he was once present, at George Eliot's home, when she and Herbert Spencer had a discussion concerning the origin of music. Crompton thought that Spencer was getting the worst of the argument and eventually he jumped up and rushed out of the room, banging the door after him! Crompton said that he enjoyed seeing the great philosopher in a temper and recognising that he was subject to the same human weaknesses as the rest of us.

In the eighties almost all Secularists were Individualists, of the Radical Individualist type which was influenced by John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer and Charles Bradlaugh. I went to greater extremes in Individualism in those days for I came much under the influence of Auberon Herbert. I shall have more to say of that charming man of fine character later.

Notwithstanding our Individualism we decided, on pursuance of our policy of a free platform, to give our audiences an opportunity to hear the best that could be said for the new Socialism which was then coming rapidly to the front. So we arranged for a lecture by H. M. Hyndman on Constructive Socialism on Wednesday, Jan. 16. 1884, and one by William Morris on Art and Socialism on Jan. 23. These were to be followed by a lecture in opposition by the Rev. J. Page Hopps on Sensible Socialism, on Monday January 28th.

Both Mr. Hyndman and Mr. Morris stayed the night at my mother's house. My brother, Ernest, and I were both at home and I remember our excitement at the thought of meeting these two well known men. We were somewhat surprised to find Mr. Hyndman in dress quite the conventional business man, frock coat, silk hat, etc., also much the same type in general manner. I believe he was on the Stock Exchange at that time. It seemed curious to hear revolutionary, even violent revolutionary, teaching given forth by such an ‘eminently respectable’ looking man! His lecture was able and very interesting but neither convincing nor persuasive to my brother and me.

The bigger event to us was the coming of William Morris. His reputation as a poet and decorative craftsman (the Kelmscott Press had not then been started) was so high that we were very definitely nervous of meeting the great man. Ernest and I went to the Station, and, two minutes after his train had come in, were at home with him and captured by his personality. It was impossible to feel constrained for many minutes in the company of Morris. He greeted us as friends, and as though we were equals, at once and immediately we were ‘at home’. His was a delightfully breezy, virile, personality. In his conversations if they touched on subjects which he felt deeply, came little bursts of temper which subsided as quickly as they arose and left no bad feeling behind them. He was not a good lecturer. His lectures were always read, and not too well read, but they were wonderful in substance and full of arresting thoughts and apt illustration. In their phrasing and general form they were beautiful.

The lecture he gave on that night in January, 1884, was soon afterwards published as one of Larner Sugden's Leek Bijou Reprints (No. 7) and was later included in Architecture, Industry & Wealth, Collected Papers by William Morris published by Longmans, Green & Co. in 1902, printed in the Golden Type of the Kelmscott Press.

After the lecture the Rev. Page Hopps, who had been in the audience, came up to supper with us. After supper we were talking about the lecture, Page Hopps sitting in an easy chair, Morris on a dinner table chair. Page Hopps said, “You know, Mr. Morris, that would be a very charming Society that you have been describing, but it's quite impossible, it would need God Almighty himself to manage it!” Immediately Morris jumped up, ran his fingers through his hair and ruffled it, walked once or twice round his chair, then, shaking his fist close to Page Hopps' face, exclaimed: “All right, man, you catch your God Almighty, we'll have him!” There was a burst of delighted laughter, in which Page Hopps heartily joined, and there was no response.

In those days of my single life I had a small smoke room adjoining my bedroom, for my mother could not bear smoking in the usual living rooms of our home. There I kept my growing collection of books and there I took visitors for a final chat and smoke before retiring for the night. When Mr. Hopps had left, Morris, my sister Sarah, Ernest, and I, went up there and had a delightful talk which I can never forget. Sarah left after about an hour but the other three of us sat talking until nearly 2 o-clock.

I am sure that one reason for this long sitting was that Morris was particularly interested in Ernest, then 19 years old and articled to the Leicester Architect Isaac Barradale, and saw something of the possibilities in him. At any rate when Ernest was anxious to have some experience in a London Architect's office, some two years later, he, after much hesitation for fear of intrusion, wrote to ask Morris's advice and perhaps a letter of introduction to a suitable Architect. At once Morris sent him three letters of introduction. Delighted and excited, Ernest took the three letters up to London, but he only had to present one, to J. D. Sedding, who at once took him into his office where Ernest stayed for two years.

While in London he joined several Societies and Committees with which Morris was actively associated, came continuously under his influence, learnt a great deal from him and was imbued with those ideals which governed the rest of his life. Between his first visit to us in 1884 and Ernest's going to London in 1886, Morris had paid us several visits and had, no doubt, become sure that Ernest would grow to something worth while under the right influence. Ernest went far and was recognised as one of the great craftsmen of his generation. I know that he always felt that he owed his great opportunity to the visits of William Morris to Leicester.

Part 2. The above comprises pages 1-24 of a 62-page typescript (with a further 40 pages of appendices).